Antimicrobial Stewardship

Antimicrobial formulary and restrictions

Key points

- An antimicrobial formulary is a simplified list of available antimicrobials within a hospital, potentially including: accepted indications for use, dosing schedules, drug interactions and side effects.

- The formulary should include a sub-set of restricted antimicrobials.

- The use of these restricted antimicrobials requires strict monitoring and adherence to the antimicrobial prescribing policy of the hospital.

- The WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics could be used as the base of an AMS restriction policy, with those falling into the Watch and Reserve groups forming targets for AMS activities.

- Auditing compliance with the antimicrobial formulary is important to ensure that the restriction polices are being adhered to.

Medication formulary

A medication formulary is a list of medicines that a hospital’s drug and therapeutic committee (DTC) (or similar) has approved for use within the facility or organisation. This list may be determined at a national, regional or local level. This list is intended to be regularly reviewed and improved, and the decision to include new medicines or exclude old medicines should be based on the recommendation of the DTC in consultation with the relevant specialty experts.

The formulary is necessary within a hospital to ensure the adequate supply of essential medicines to treat the range of diseases that is seen within the patient population and satisfy the priority health care needs of the population. As many medicines may have overlapping spectrums of activity or have questionable ability to treat the intended diseases, there is a requirement within healthcare systems to develop screening processes for medicines that are allowed to be prescribed and to ensure that those selected for the list are the safest and most effective medicines, and have public health relevance and comparative cost-effectiveness.

There are many benefits for having a well-developed formulary. These include:

- improved procurement processes;

- easier inventory management;

- decreased healthcare costs;

- reduced adverse drug reactions; and

- improved patient care.

The formulary system can also be used to influence the prescribing practices of staff by restricting access to certain medicines by applying strict governance criteria for their use. A formulary that includes a sub-set of restricted antimicrobials is a core component of an effective AMS program. If a facility does not already have a formal medication formulary, developing the antimicrobial formulary might be a good starting point for this. There will need to be consideration of how it will fit into the broader medication formulary workflow, and it may be worth having a medication formulary working party, to guide the development and implementation process.

Antimicrobial formulary

An antimicrobial formulary is a simplified list of available antimicrobials, with accepted indications for use, dosing schedules, drug interactions and side effects. A robust formulary will allow for easier maintenance of guidelines, and provision of education and training. Available antimicrobials will have been evaluated in a systematic manner and meet strict criteria for inclusion. This will also benefit prescribers by limiting the number of antimicrobials that they will have to learn how to utilise, and, therefore, should improve the appropriateness of prescribing.

The antimicrobial formulary list should include the antimicrobials suggested in the WHO’s current Model List of Essential Medicines

or the national essential medicines list if available, with local or regional adaptation based on local infection patterns, resistance profiles of common organisms, and drug availability and affordability.

The Model List is a guide for the development of national and institutional essential medicine lists. Essential medicines are a powerful means to promote health equity. The majority of countries will have a national list that includes antimicrobials. Some may even have regional or state lists. National guidelines for infections and the use of antimicrobials should relate closely to the national list of essential medicines.

Antimicrobial formulary management

The DTC, or similar, has the responsibility of creating and managing the antimicrobial formulary list but may involve an antimicrobial sub-committee or rely on the AMS team to advise on the need for adding new antimicrobials or indications to the current list. Principles of antimicrobial formulary management include:

- Antimicrobials will be selected on their ability to treat the relevant infectious diseases of the country or region.

- The formulary should be consistent with any national formulary or approved standard infection treatment guidelines.

- The formulary should be reviewed and revised periodically.

- Combination/fixed-dose antimicrobials should only be used in specific proven infections (e.g., tuberculosis or HIV).

- The ability to prescribe antimicrobials is restricted to only those practitioners with appropriate prescribing skills.

The management of the antimicrobial formulary should involve periodical review and revision of the list by the DTC; at least monthly to three-monthly would be preferable, but less often may be acceptable if small numbers of changes are expected. This process should involve, if available, medical and pharmacy staff knowledgeable about (and able to evaluate) the spectrum of activity of antimicrobials, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, hospital antibiograms, and common infectious diseases. If only a small hospital is managing a local formulary independently, it may be worth considering collaborating and sharing resources with other similar local facilities to establish a joint committee and reduce the duplication of material and resources.

New antimicrobials should be added if they meet the criteria for inclusion, including:

- acceptable data on safety, pharmacological action, adverse drug reactions, and drug interactions;

- reasons why this is superior to current formulary-listed antimicrobial(s);

- scientific evidence and literature to support its addition;

- updated clinical guidelines or treatment pathways;

- altered country or hospital infection patterns and antibiogram;

- acceptable cost-efficiency; and

- approved and quality source of supply.

Current antimicrobials should be removed from the list if they meet the deletion criteria, including:

- the antimicrobial is no longer used;

- recent data on lack of safety, efficacy, quality, etc., has become available; and

- the antimicrobial does not meet the requirements for cost-effectiveness, if an acceptable alternative is identified.

The AMS team should seek the support of and advocacy from the executive of the hospital and key policy-makers to encourage the formulary's uptake, use and acceptance by all prescribing staff within the hospital. At all times, the formulary should remain ethically sound, and any influence or pressure by the pharmaceutical industry should be excluded from all management decisions by the DTC.

Stock shortages

Stock shortages are becoming a global issue. Often, they occur unexpectedly, with antimicrobials being a common class of medicines affected. Antimicrobial stock shortages are known to adversely affect clinicians' ability to treat infections, medication safety and resistance rates; and increase the cost of stock purchasing and resources required to manage shortages.

Timely communication from suppliers facilitates quicker local responses to stock shortages. Locally, there is a need to have a co-ordinated system to quickly respond to stock shortages.

This should include the following:

- Review of current stock on hand and duration of expected use before stock runs out.

- Pharmacy departments are often well placed to do this.

- Communicate possible stock shortage situations to stakeholders, including medical staff (ID specialists if available), early so that they can prepare.

- Conduct clinical review and provide recommendations for alternatives.

- This may be based on indication and severity of infection.

- Alternatives can include using other strengths and dose forms, and other antimicrobials with a similar required spectrum of activity; and undertaking early intravenous-to-oral switches.

- Consider the practical implications of the alternatives recommended, including storage, quantity and cost.

- Options to respond to shortages:

- use emergency stock;

- procure stock through other means or access schemes;

- use an alternative brand;

- use a different dose, form or strength;

- use an alternative medicine of equal efficacy;

- use second- or third-line medicines; and

- borrow stock from another hospital or pharmacy.

Some practical questions to ask:

- Who is currently prescribing the drug (what wards or units)?

- For which indications is it being used?

- Is that use appropriate?

- A brief audit may be helpful to better understand this.

- E.g., look back over 20 or 30 prescriptions of that drug.

- Can we rationalise its use?

- Is earlier intravenous-to-oral switch possible, especially for agents with high oral bioavailability?

- Review durations of use: are prescribers using unnecessarily prolonged courses?

- Is there any unnecessary use, e.g., any cases of prolonged post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis that is not necessary?

- Are there other appropriate alternative drugs, and are they in stock?

- E.g., for cefazolin, use cefalotin.

- E.g., for ampicillin, use amoxicillin.

- Are there indications for which there is no appropriate alternative (i.e., we want to reserve the drug for these high-risk conditions)?

- E.g., intravenous acyclovir for presumed or proven encephalitis.

- E.g., intravenous benzylpenicillin for neurosyphilis.

- E.g., gentamicin for enterococcal endocarditis.

- Can we recommend appropriate replacements or combinations of replacements that might vary by indication? E.g., for metronidazole shortage:

- alternative agents to treat anaerobic infections might include clindamycin, amoxicillin-clavulanate or piperacillin-tazobactam.

Offering several options may help limit the impact on the alternative drug. For example, during a piperacillin-tazobactam shortage, a shortage of cefepime soon followed when a direct switch was promoted. Instead, offer a few alternative regimens to ‘spread the load’.

Managing the shortage

- A clear communication plan is key to managing a shortage.

- A written poster can be very useful so that the plan is clear.

- Examples of these fact sheets can be found on our website here.

- Talk to executive.

- Talk to clinical leaders and senior doctors.

- Talk to nurse unit managers.

- Ask them to communicate information to their teams at ward and unit meetings.

- Where is the drug stocked?

- Can we remove the drug from that location and put the alternative drug (and the information about the issue) in that location?

- Think about wards, emergency department, theatres, etc.

In some circumstances, the drug in short supply can be listed as 'restricted'. Approval for use may need to be obtained from a nominated expert or group of experts. Have a clear process for how this approval should be obtained, e.g., contact through a nominated pager or phone number, and have strategies for after-hours access. For example, in a vancomycin shortage, any use beyond 24 hours should require approval from the infectious diseases department, DTC, etc.

Anticipate the impact on the alternative drugs and monitor their supply too. For example, teicoplanin shortages follow vancomycin shortages. Obtain updates from suppliers and review the situation regularly. Communicate information to staff via multiple means and the most effective avenues, e.g., via e-mail and phone messaging applications; and to senior medical staff. A regular update (e.g., weekly) may be appropriate. Once clear lines of communication have been established, these ideally can be re-activated whenever future stock shortages occur to help streamline the process.

Non-formulary medicines

It should be possible to prescribe non-formulary medications when the formulary choices are not suitable or available. All formulary systems need to allow for the introduction of a non-formulary antimicrobial on a limited basis if the need arises. This is usually to treat a single patient or when there are short-term medicine shortages. The system needs to be put into place so as to allow the procurement of these necessary antimicrobials for short-term use but still maintain the integrity of the formulary system to prevent inappropriate use of antimicrobials.

Management of these non-formulary antimicrobial include:

- limiting the number of non-formulary antimicrobials to only those essential for treatment;

- limiting access to only those prescribers who are appropriately qualified to be requesting these antimicrobials; and

- keeping a register of all non-formulary medicines used and reviewing these at the DTC meetings.

Formulary manual

The formulary manual is the resource publication where all the elements of the formulary are outlined and made available to prescribers. There should be an alphabetical listing of all medicines on the formulary, classified according to their therapeutic classes. The manual is not intended to be a complex document that is only available to hospital executives; it is intended to be a practical resource and available for all staff in an easily accessible form. This could be formatted as a pocket guide, posters in high-use areas, or an internal electronic resource. The manual needs to be updated and distributed regularly to allow staff to keep up with changes in the formulary. It should also outline the process for accessing non-formulary medicines or requesting the addition of antimicrobials onto this list.

For the antimicrobial therapeutic class or for each antimicrobial listed, the formulary should include:

- generic name;

- dosage schedule and formulations; and

- indications for approved use, including rational drug use information (e.g., IV-to-oral switch, de-escalation, etc.).

If access to standard drug reference material is difficult, the formulary may also include:

- contraindications, adverse drug reactions, drug interactions, etc.;

- prescribing information for children and the elderly, and for renal failure;

- storage guidelines;

- instructions and warnings on preparation and administration; and

- specific guidelines on the use and administration of the antimicrobial.

Other useful information that may be listed includes:

- price;

- regulation category;

- brand names and synonyms;

- labelling information; and

- patient- and carer-counselling information.

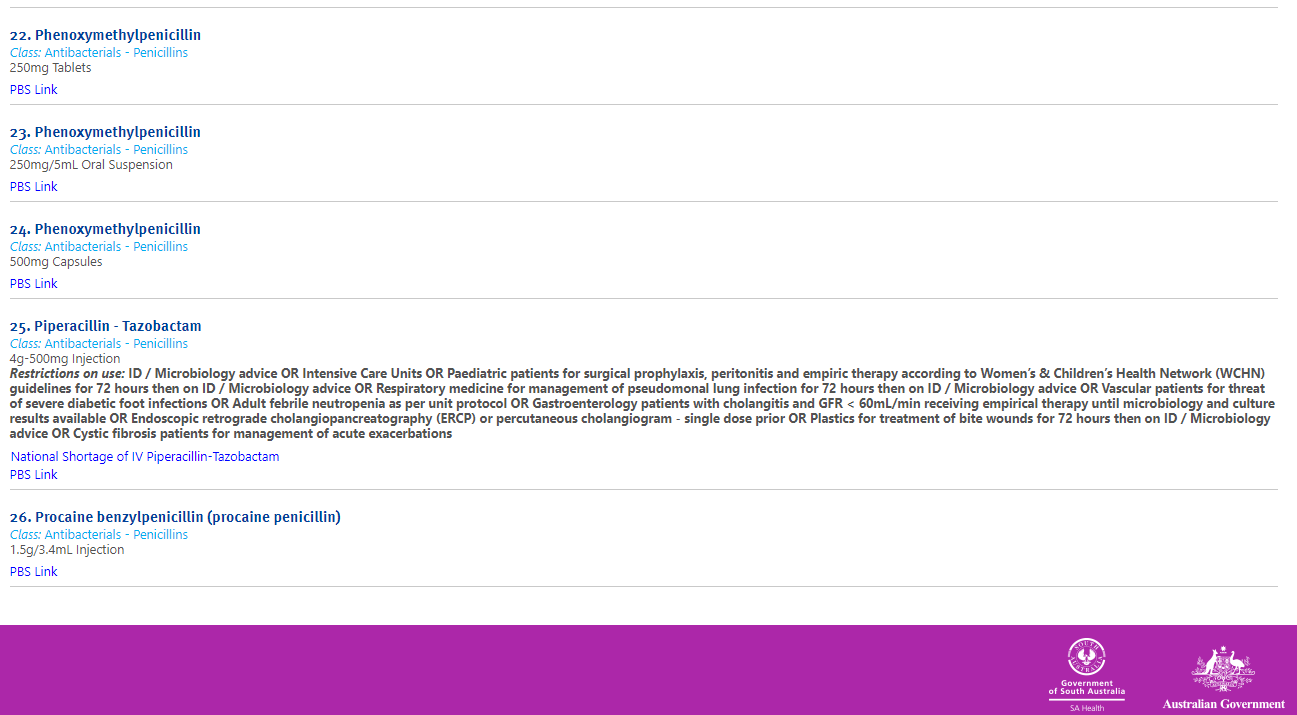

An example of an antimicrobial formulary

Government of South Australia. SA Health medicines formulary, Government of South Australia.

Antimicrobial restriction policies

Restricted antimicrobials include those that meet the restriction policies of the hospital to limit their use, as defined by the DTC in consultation with the AMS committee. The use of these restricted antimicrobials requires strict monitoring and adherence to the antimicrobial prescribing policy of the hospital. It may be decided that they can only be prescribed in consultation with an infectious diseases specialist, clinical microbiologist or the AMS team.

Restriction policies may include certain drugs based upon:

- spectrum of activity of the antimicrobial (last-line agent);

- cost of the antimicrobial; and

- potential for toxicity.

The restriction policy may describe that the drug can only be used:

- by a particular specialty or unit of the hospital;

- for particular pathogens or conditions;

- for situations when the resistance profile of the organism precludes other options;

- for situations where other options are contraindicated (allergies, drug intolerance, drug interactions, etc.); and

- where there has been demonstrated treatment failure with other options.

Authorised prescribers within the hospital should be encouraged to prescribe antimicrobials only in line with the AMS policy, endorsed by the executive. This should support the prudent and appropriate use of antimicrobials, and ensure that antimicrobials are prescribed in line with any national or local prescribing guidelines, directing use to the narrowest-spectrum agent recommended. An approval system is a method to enforce these policies and guide prescribers to use the most appropriate antimicrobial at all times.

All restricted antimicrobials that are being prescribed and used within the hospital need to be closely monitored, reviewed and reported on. This is to determine that only authorised prescribing staff members are accessing these medicines and that they are being used appropriately.

Developing a restriction procedure

It is important to develop an antimicrobial restriction policy and procedure document that clearly outlines what is expected of clinical staff who are prescribing, dispensing and administering restricted antimicrobials. This document should be incorporated into the antimicrobial prescribing policy of the hospital, and should include the following extra information:

- a statement from the executive outlining support for the policy and how all prescribers are required to abide by the restriction protocols;

- how medical officers should obtain antimicrobial approvals prior to prescribing restricted antimicrobials;

- any relevant drug order forms;

- pharmacists' responsibility to check that an approval has been obtained prior to dispensing the antimicrobial;

- nurses' responsibility to check that an approval has been obtained prior to administering the antimicrobial; and

- what to do if there is no approval:

- who to contact;

- whether the first dose can still be dispensed and administered; and

- whether there is a 24-48 hour grace period to cover out-of-hours prescribing.

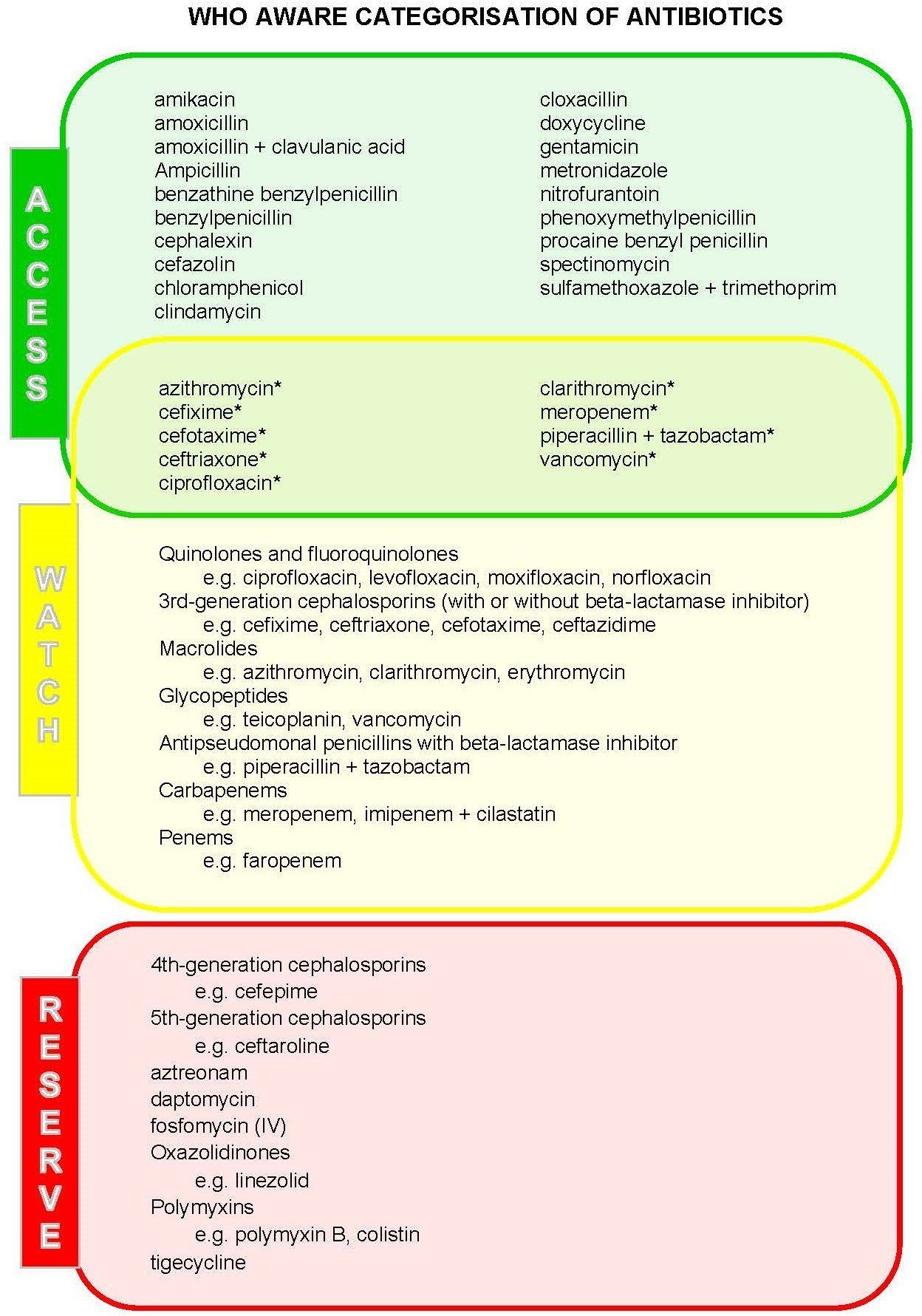

WHO AWaRe categorisation

As part of the WHO’s global strategy to combat AMR, there is a requirement to optimise the use of antimicrobials, while ensuring that universal access to safe, effective, quality and affordable medicines is maintained. For the 2017 update to the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the Expert Committee identified a list of infections that were thought to be broadly applicable to the majority of countries. Only treatments for common infections were considered and empirical first- or second-line therapy choices were identified.

To further assist in the development of tools for AMS programs at local, national and global levels, the Expert Committee also categorised antibiotics into three groups, with the intention of ensuring improved access and clinical outcomes, reducing potential for the development of AMR, and preserving the use of the ‘last-resort’ antibiotics for those who require them. These were the ‘Access’, ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’ antibacterial groups.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Access | The Access group are those that are first- or second-line empiric therapy for many common indications. They are generally narrower-spectrum with low risk of toxicity. These should be readily available at all hospitals with the appropriate quantity, quality, formulation and at a reasonable price. Selected Access antimicrobials are also included in the Watch group. |

| Watch | The Watch group are those that are thought to have greater risk of toxicity, or higher potential to induce resistance. These agents should have prioritised targets for AMS programs to limit their use to only recommended indications. |

| Reserve | The Reserve group are those that are regarded as ‘last-resort’ options, e.g., for serious or life-threatening infections due to multi-drug resistant bacteria. These are intended to be protected against inappropriate use through strict restriction and approval programs. |

The intention of the AWaRe list is to be revised over time and to be adapted locally according to the prevalence of diseases and local antibiograms. Those antimicrobials that fall into the Watch and Reserve groups could be targets for AMS activities, including monitoring of use, development of guidelines, and inclusion in approval systems and educational activities.

The recommendations in the Model List are not intended to be guidelines, and the empirical choices suggested may need to be adapted according to national and local specifications, including the availability of certain antimicrobials, and local resistance patterns. These are also not intended to replace clinical judgement and each patient should be assessed and treated as clinically indicated.

Restricted antimicrobial approval systems

The restriction of certain antimicrobials, with a strict approval process to oversee their use, is a process by which the formulary can be effectively implemented, controlled and monitored. The implementation of hospital AMS programs that incorporate a restricted antimicrobial approval system have been shown to be associated with:

- decreased quantity of restricted antimicrobials prescribed;

- reduced drug expenditure;

- decreased lengths of stay;

- improved resistance profiles of certain local pathogens; and

- more appropriate empirical antimicrobial choices.

Methods for managing an antimicrobial approval system

In order to effectively manage an antimicrobial approval system, there needs to be a clearly outlined structure for gaining approvals that is easy to administer and acceptable to all parties. The specific mechanism through which this is achieved will be dependent on its suitability to the workflow of the hospital and the availability of resources. Approvals are usually required pre-prescription and in some cases may be required prior to use.

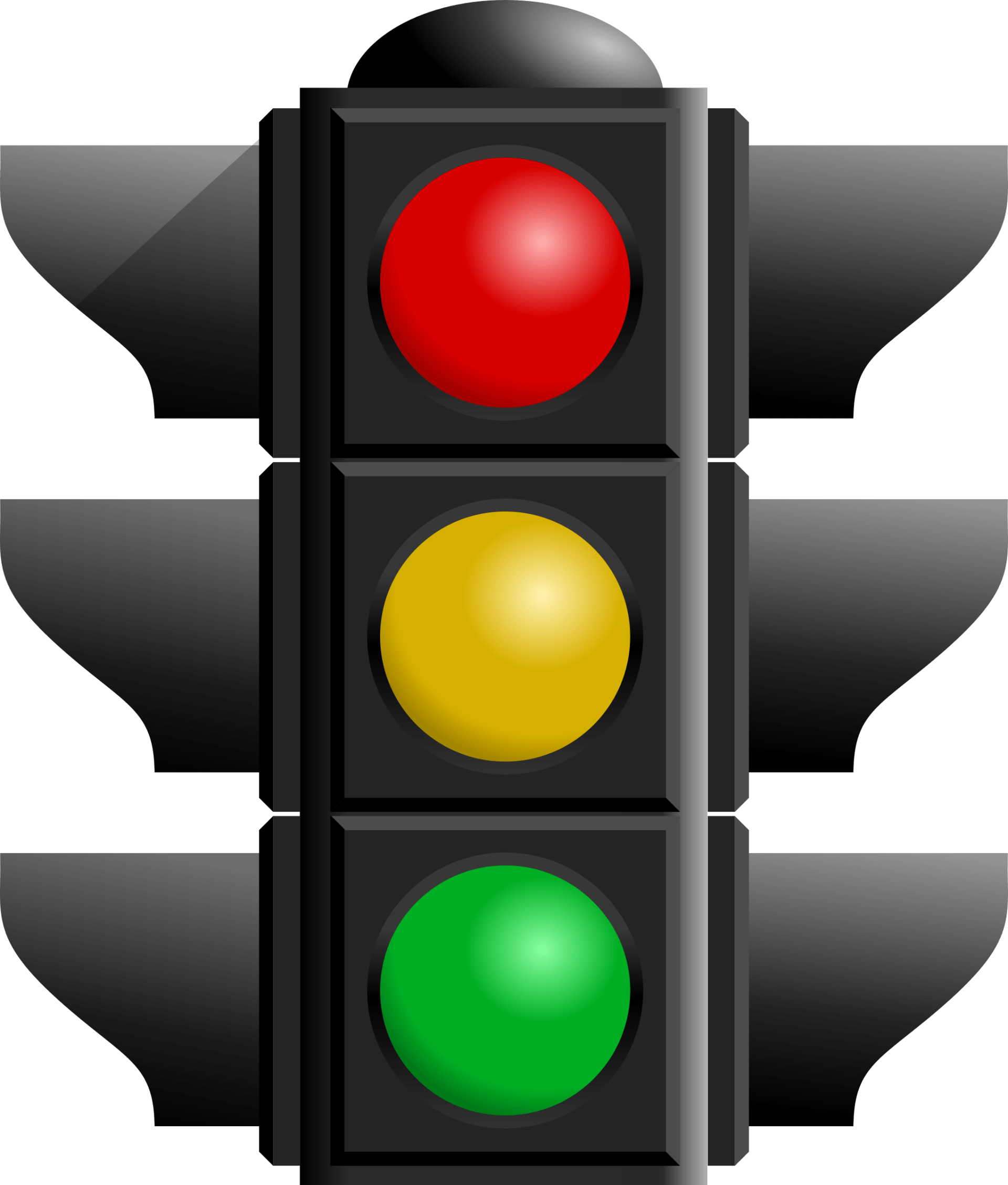

Traffic light system

The traffic light system is a common way that many organisations classify their antimicrobials according to requirements for approval of use. The traffic light system is a visual representation of these requirements, into red, amber and green classifications. The different colours correspond to the level of restriction for that antimicrobial or class.

Red: Red antimicrobials are those that are highly restricted. They may be restricted because they have a very broad spectrum of activity or may be seen as a ‘last-resort’ treatment option for specific patient groups or disease conditions. They may also be restricted due to a high toxicity risk or cost. These antimicrobials can usually only be prescribed by an expert, or require expert approval (e.g., by an infectious diseases physician, microbiologist or by the hospital administration) prior to being prescribed or administered. Examples include colistin and linezolid.

Amber: Amber antimicrobials are those that have a lower level of restriction. They may be prescribed without restrictions for certain defined indications or clinical conditions but must be approved prior to use for other conditions that are not listed, or for extended duration of therapy, per the highly restricted ‘red’ antimicrobials. These are generally antimicrobials that have an associated toxicity risk or the potential to induce resistance but are recommended as first- or second-line agents in the hospital's recommended guidelines. Examples include vancomycin, ceftriaxone and piperacillin-tazobactam.

Green: Green antimicrobials are those that have no restrictions on their use. They may be prescribed without approval. They are generally narrow-spectrum antimicrobials with low potential to induce resistance and are commonly listed as first-line agents in the hospital's recommended guidelines. Examples include amoxicillin and cefazolin.

The categorisation of antimicrobials may vary depending on the type and size of the hospital, and the expertise of prescribers. In small hospitals, antimicrobials such as meropenem and vancomycin would likely be categorised as red drugs. These may be used rarely, and the prescribers may lack expertise and familiarity with them. Discussions with an expert are, therefore, required before prescribing is approved. In other settings (e.g., large major-city hospitals), they may be managed as amber drugs, with approval required for prolonged use (e.g., >3 days) only. The allocation of drugs to each category does depend on the case-mix of patients at the hospital, and the availability of expertise and resources relative to the caseload or numbers of likely patients.

Auditing of compliance with the antimicrobial formulary and approval system

Auditing compliance with the antimicrobial formulary is important as the AMS team needs to ensure that the restriction polices are being adhered to. The following may be measured:

- how many requests for approvals to use restricted antimicrobial are received;

- how many prescriptions for restricted antimicrobials received approval versus how many were rejected; and

- how many restricted antimicrobials were dispensed and administered without an official approval.

It may be difficult or time-consuming to determine if the formulary system is being adhered to appropriately. The required information may be stored in multiple locations and a hospital may have limited ability to connect dispensing information to individual patients. If hospitals have the ability to use electronic medication management or approval systems, this will allow for greater ease of auditing.

Minimum prescribing standards for a prescribing procedure

The antimicrobial prescribing policy should contain a statement regarding the minimum standards for prescribing. This can include some quality requirements to ensure patient safety.

For every antimicrobial prescribed, there should be a clearly documented:

- start-date for the prescription;

- name of the antimicrobial (this should ideally be the generic name, not the trade name);

- intended route of administration;

- required dose;

- required frequency of administration;

- printed name of the prescriber; and

- signature of the prescriber.

To facilitate AMS activities, the patient's medical notes should include documentation of:

- the indication for the antimicrobial;

- the intended stop-date, or a review-date for the antimicrobial;

- if not compliant with the recommended guidelines, a justified reason for any deviation; and

- any need for therapeutic drug monitoring.

This will allow enhance the quality and safety of prescribing for the patient, and enable AMS reviews and interventions.

Medication management charts

The process of documenting a medication order and its administration can often be cumbersome and confusing, with significant opportunities for errors to occur. When there is no dedicated medication chart for prescribing and administration, duplication of medication information may occur, allowing for introduction of unnecessary and dangerous medication errors and potential misinterpretation of prescribers’ intentions. It is recommended that for the quality and safety of prescribing a standardised medication chart is introduced, preferably nationally, whereby the medication order and administration are directly written onto the same document.

Having a nationally endorsed standard medication chart will support the delivery of appropriate antimicrobials to hospitalised patients, and reduce the risk of prescribing, dispensing and administration errors by standardising the presentation of drug information. The charts should consist of required elements and layouts, while allowing for some local modifications as necessary. Electronic medication management systems, if available, should then incorporate the required elements as a minimum safety feature. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s national inpatient medication chart is a good example of such a chart and could be adapted for local use.

In the absence of a national medical chart, if resources allow, a local standardised medication chart should be developed. The absence of a dedicated medication chart is likely to inhibit many AMS activities; for example, post-prescription review or prospective audit and feedback would be very time-consuming and susceptible to errors. The benefits of introducing a standardised drug chart would extend far beyond antimicrobial prescribing. It would substantially reduce medication errors relating to delayed or missed administration, extended durations, transcription errors and documentation of allergies. Medication charts help to communicate information effectively and consistently between clinicians on the intended use of antimicrobials for a patient.